More Information

Submitted: January 20, 2025 | Approved: February 13, 2025 | Published: February 14, 2025

How to cite this article: Tshimbombu TN, Olarinde I, Wiggins J, Vergo M. Euthanasia: Growing Acceptance amid Lingering Reluctance. Clin J Nurs Care Pract. 2025; 9: 001-006. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.cjncp.1001058.

DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjncp.1001058

Copyright License: © 2025 Tshimbombu TN, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Keywords: Eumori; Euthanasia; Physician-assisted suicide; Physicians; Public

Abbreviations: Physician-Assisted Suicide

Euthanasia: Growing Acceptance amid Lingering Reluctance

Tshibambe N Tshimbombu1, Immanuel Olarinde2, Judea Wiggins1* and Maxwell Vergo3

1Department of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, Arizona, USA

2College of Medicine, Richmond Gabriel University, St. Vincent and the Grenadines USA

3Section of Palliative Care, Department of Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire, USA

*Address for Correspondence: Judea Wiggins, MD, Department of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, 350 W Thomas Rd, Phoenix, Arizona 85013, USA, Email: [email protected]

Euthanasia has long been a contentious topic. Societal acceptance and legalization of euthanasia have increased over the past decades but still lag behind that of physician-assisted suicide (PAS). Euphemisms such as “death with dignity” have facilitated the integration of PAS into end-of-life discussions with reduced stigma. We hypothesize that the persistent use of the term “euthanasia” hinders open, compassionate communication about this practice, particularly among healthcare professionals who adhere to the ethical principle of nonmaleficence. To address this issue, we propose the adoption of euphemisms, such as “eumori,” meaning “good death,” similar to the terminology used in PAS. These proposed terms mitigate the negative connotations associated with euthanasia. This approach serves as an initial yet significant step toward reframing euthanasia within the context of end-of-life care. Further research and dialogue are essential to explore and address other barriers to broader acceptance of euthanasia as a viable end-of-life option.

Euthanasia, which stems from the Greek word “EY-ΘANATO∑” for “good death,” has been a contentious topic for more than 3,000 years [1]. It refers to the deliberate termination of a person’s life with their explicit consent, specifically of individuals with terminal illnesses or incurable conditions. Euthanasia is distinct from physician-assisted suicide (PAS), which refers to the self-administration of a life-ending medication received from a physician (Table 1) [2]. Euthanasia includes a diverse array of practices influenced by cultural, religious, ethical, and legal considerations [3,4]. It has encountered vehement opposition, both in legal frameworks and societal discourse, at least in part because of its historical misuse [3,4]. For example, in Nazi Germany, individuals with mental and physical disabilities were killed in the name of euthanasia [5]. Blurring the lines between euthanasia and eugenics perpetuates further condemnation of its use [5].

| Table 1: Difference between euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide [2-4]. | |

| Term | Definition |

| Physician-assisted suicide | The deliberate action by a mentally competent patient who independently requests life-ending medication from a physician to self-administer and end their life without any external influence. |

| Euthanasia | |

| Active euthanasia | The intentional act by a medical professional or layperson to accelerate a patient’s death, usually through the administration of medication, to alleviate suffering from a terminal or incurable condition. |

| Voluntary active euthanasia | Form of active euthanasia that must be carried out at the explicit request of a mentally competent patient. |

| Non-voluntary active euthanasia | Form of active euthanasia where the patient lacks decision-making capacity and the choice is made by their next of kin. |

| Involuntary active euthanasia | Form of active euthanasia where a patient’s death is hastened against their wishes or without their consent, including the absence of consent from a surrogate. |

| Passive euthanasia | The deliberate decision by a medical professional or layperson to accelerate a patient’s death by intentionally withholding interventions that would have otherwise preserved the patient’s life. |

In recent years, however, there has been a noticeable surge in the legalization of euthanasia and a shift in global public opinion toward support of this practice. Since euthanasia was legalized in the Netherlands and Belgium in 2002, other countries, including Luxembourg, Colombia, and Canada, have followed suit (Table 2) [6]. The latest addition to this list is Cuba, which legalized euthanasia in December 2023 [7,8]. Discussions regarding the potential legalization of euthanasia are underway in many countries, including Italy, Sweden, and Finland [9]. In addition, data from several studies indicate an increasing public opinion in favor of legalizing euthanasia for chronically ill patients, particularly in Western Europe [2,9-11].

| Table 2: Countries with full legalization of euthanasia [6]. | ||

| Countries | Year of Legislation | Type of Legislation |

| Netherlands | 1994 | Legal review procedure |

| 2002 | Legislation | |

| Belgium | 2002 | Legislation |

| Luxembourg | 2009 | Legislation |

| Colombia | 2014 | Court ruling |

| Canada | 2016 | Legislation, National |

| Legislation, Quebec | ||

| Australia | ||

| Victoria | 2017 | Legislation |

| Western Australia | 2019 | Legislation |

| Spain | 2021 | Legislation |

| New Zealand | 2021 | Legislation |

| Portugal | 2023 | Legislation |

| Cuba | 2023 | Legislation |

However, whereas the public’s approval of euthanasia has been steadily increasing, healthcare providers have shown ambivalence and hesitance [2,9]. We hypothesize that this reluctance could stem from the stigma associated with the term “euthanasia.” Therefore, we suggest exploring alternative wording to alleviate the burden of historical negative connotations linked to euthanasia. Drawing parallels within the context of PAS, where terms such as “medical assistance in dying” and “death with dignity” have been employed to soften the impact of the terminology, acceptance of a euphemism for euthanasia could facilitate constructive conversations around end-of-life decisions.

This article examines public and clinician perspectives and attitudes toward euthanasia. It also considers whether adopting an alternative term could help alleviate the challenges facing healthcare professionals when providing end-of-life care. Thus, we aim to contribute to a deeper understanding of the multifaceted ethical, cultural, and legal considerations surrounding end-of-life choices.

Public attitudes

Public attitudes toward euthanasia have evolved across different regional areas. In particular, there is growing support for its use in the U.S. and especially in Western Europe [2,9].

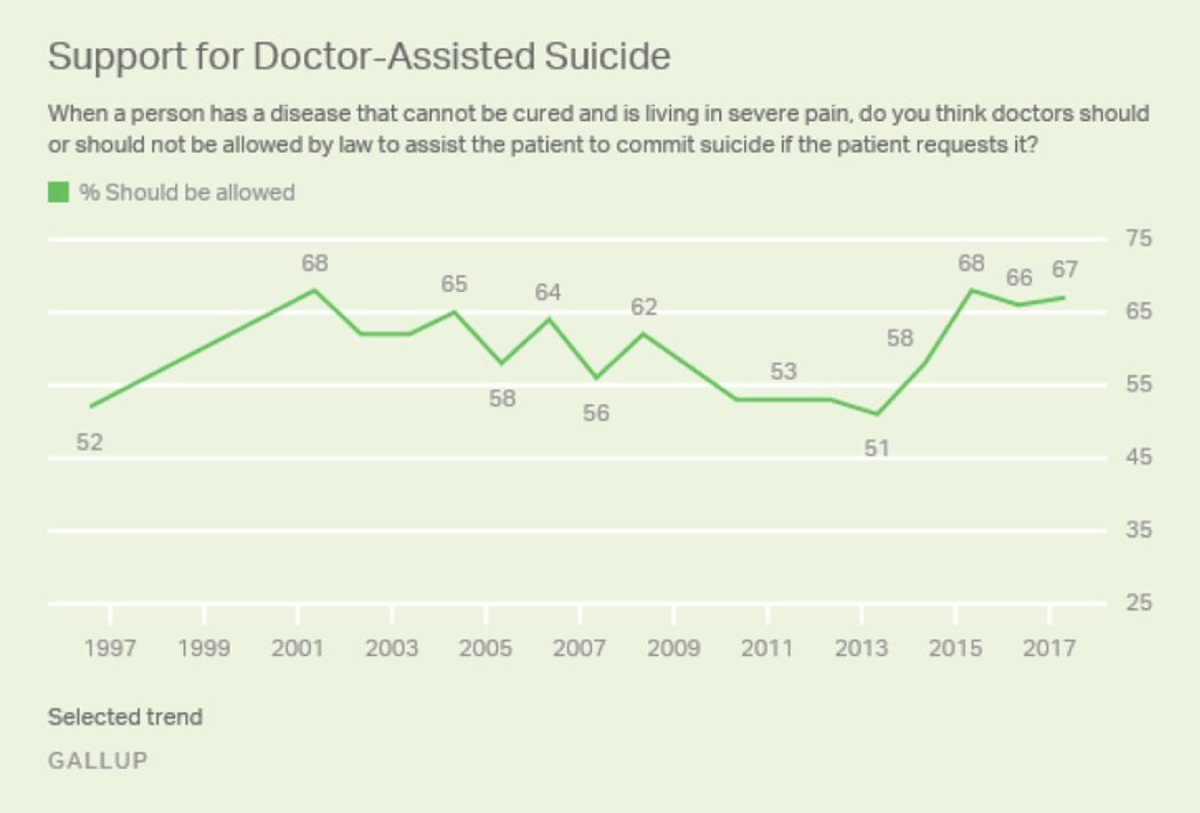

In the U.S., Gallup surveys have tracked public opinion on euthanasia since 1947. These surveys ask whether doctors should be permitted by law to end a patient’s life by painless means if requested by the patient and their family [12,13]. Results have shown that support for euthanasia increased steadily over the decades, from 37% in 1947 to 53% in 1973 and 63% in 1990 [2]. Although support for euthanasia peaked at 75% in 2005 and fell back down to 64% in 2012, acceptance rose again to 73% in 2017 (Figure 1) [12,13], which is nearly double the initial level of support in 1947.

Figure 1: Americans’ public support for euthanasia [12]. Used with permission from McCarthy J, Wood J. Majority of Americans Remain Supportive of Euthanasia.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/211928/majority-americans-remain-supportive-euthanasia.aspx. Accessed July 31, 2024.

In Europe, a pivotal event in the Netherlands sparked a profound debate on euthanasia in 1973 when Andries Postma euthanized her terminally ill mother [14]. This act catalyzed a dramatic increase in societal acceptance of euthanasia from 50% in 1966 to 90% by 1990 [15]. The momentum generated by public support ultimately led to the legalization of euthanasia in the Netherlands in 2002 under the Dutch Euthanasia Act [15]. Subsequent research revealed that 60% of the Dutch public believed individuals with advanced dementia should be eligible for euthanasia [16]. Most recently, in the Netherlands, former Dutch Prime Minister Dries van Agt and his wife chose dual voluntary active euthanasia in 2023 [6,15,17]. Acceptance of euthanasia has extended to other Western European countries that enacted euthanasia laws, such as Belgium, Luxembourg, Spain, and Portugal [6]. Of note, Finland saw an increase in public acceptance of euthanasia from 50% to 85% between 1998 and 2017 [9].

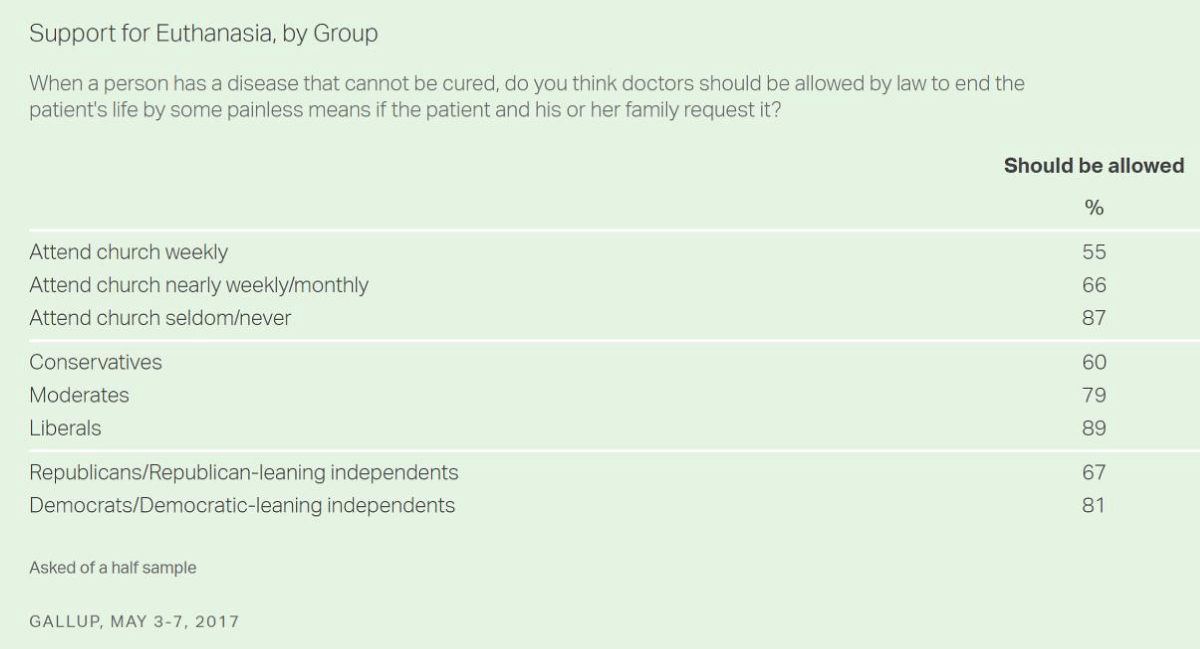

Support for euthanasia is also growing beyond the U.S. and Europe, as countries such as Canada, Cuba, Colombia, and certain regions in Australia and New Zealand have legalized euthanasia. This increase in support for euthanasia can be attributed to factors such as liberalism, younger demographics, higher literacy rates, and lower religiosity (Figure 2) [2,12,13]. It reflects a global trend toward more progressive end-of-life care policies and signals a shift toward greater respect for individual autonomy in healthcare decision-making.

Figure 2: Support for euthanasia in the U.S., by group* [12,13]. *Based on telephone interviews conducted May 3-7, 2017, with a random sample of 518 adults age 18+ living in all 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. Used with permission from McCarthy J, Wood J. Majority of Americans Remain Supportive of Euthanasia. Gallup, Inc.

https://news.gallup.com/poll/211928/majority-americans-remain-supportive-euthanasia.aspx. Accessed July 31, 2024.

Physician perspectives

Physicians’ attitudes toward euthanasia differ from those of the general public and often result in lower levels of support on surveys [2,9] Over time, the percentage of physicians fully endorsing the legalization of euthanasia rose dramatically, from 5% in 1993 to 25% in 2020 [9]. However, the proportion of physicians expressing no opinion decreased from 19% to 5% during the same period, while those disagreeing entirely with euthanasia legalization also slightly increased, from 30% to 34% [9].

Surveys of physicians conducted across the U.S., Europe, and Australia consistently demonstrate lower levels of support for euthanasia than that of the general public [2,9]. In countries such as Italy, where euthanasia remains illegal, only 36% of physicians express support for the practice [2]. In contrast, support among physicians is stronger in countries such as the Netherlands and Belgium, where euthanasia is legal [9]. In addition, a substantial percentage of physicians in these countries express willingness to perform euthanasia under certain circumstances. For example, 86% of physicians in the Netherlands and 81% of physicians in Belgium stated they could envision performing euthanasia.

Notably, studies have shown varying levels of acceptance among physicians regarding euthanasia for patients with advanced dementia [2,16,18]. Some physicians consider it acceptable under certain conditions, such as among people with severe comorbidities or those who have written advance directives, whereas others are strongly opposed to the idea [2,16,18]. Various studies have found differing reasons for physicians’ reluctance toward the concept of euthanasia, suggesting there is no universal explanation. For instance, Brinkman-Stoppelenburg et al. identified the emotional toll associated with the procedure as a concern among physicians [16]. Similarly, Kouwenhoven, et al. reported that some physicians feel uneasy about performing euthanasia because they perceive the decision-making process as outside their realm of responsibility, particularly in cases involving dementia [18]. Additionally, physicians prioritize the principle of nonmaleficence and, therefore, prefer to ensure the voluntariness of the patient before proceeding with any end-of-life intervention [2].

Overall, physicians’ attitudes seemed to be more nuanced and displayed ambivalence or showed less support than the general public did for euthanasia. The reasons behind this disparity are not clear. We hypothesize that the negative connotations associated with the vague term “euthanasia” may contribute to ethical concerns among healthcare providers when discussing it as a clinical option. These concerns may also be a significant barrier to legalization. We also believe further research is needed to improve our understanding of these complexities and their implications for end-of-life care decision-making.

The authors’ perspective: Changing terminology

An in-depth analysis of 33 clinician-family meetings held in neonatal, pediatric, or pediatric cardiac intensive care units revealed that only 8% of references to death used direct terms such as “death,” “die,” “dying,” or “stillborn” [19]. The remaining 92% of references were categorized as euphemisms, where speakers opted for softer language such as “pass away” [19]. This pattern is particularly noticeable in discussions surrounding PAS, where a plethora of evidence suggests that obstacles to the legalization of PAS can, at least in part, be attributed to terminology. Opponents of PAS strategically aimed at discrediting the practice focused on the term “assisted suicide” [20-22]. The American College of Legal Medicine actively opposed this terminology and submitted an amicus brief to the United States Supreme Court in 1996 advocating for the elimination of the term “suicide” from these discussions [20-22]. This advocacy effort resulted in notable changes, including the adoption of alternative terminology such as “death with dignity,” as demonstrated by Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act in 1997. Over the subsequent decade, similar terminology gained acceptance in 10 other authorized jurisdictions, further promoting the legal advancement of PAS over euthanasia. These developments underscore the significant impact that changes in terminology can have in mitigating negative connotations associated with end-of-life practices.

Therefore, we advocate for the use of euphemisms as a first step to overcome euthanasia’s negative perceptions. One example of such a euphemism is the term “eumori.” With its blend of Latin and Greek roots of “eu,” signifying good, and “moris,” meaning death, “eumori” effectively encapsulates the essence of euthanasia while imbuing it with notions of dignity and compassion. This term not only offers a culturally resonant expression of euthanasia but also represents a departure from its contentious history. We believe the use of such euphemisms, as in the case of PAS, can ultimately reshape the discourse surrounding end-of-life care. This shift might also prompt further exploration of factors beyond terminology that hinder healthcare providers from aligning with the general public’s approval and comfort level regarding euthanasia.

Feasibility of acceptance of euthanasia and the change in its terminology

The complexities surrounding euthanasia pose significant challenges to the adoption of our perspective as medical and social practices. These challenges are fundamentally shaped by sociocultural, legal, and ethical considerations, which differ across regions and cultures. Such constraints continue to influence public perception, decision-making, and the broader discourse surrounding euthanasia. Thus, softening the language away from its historically loaded and negative associations may alleviate some of the moral and ethical burdens tied to its discussion. However, despite this perspective, constraints persist, as some may still perceive the term as inherently linked to past atrocities, associating it with the practice of evil.

Sociocultural constraints

The sociocultural environment plays a crucial role in determining the acceptance of euthanasia. In many societies, attitudes toward euthanasia are deeply rooted in historical, religious, and cultural beliefs. One of the most notable barriers is the historical connotation of euthanasia, particularly its association with the Nazi regime’s use of “mercy killings” during the Holocaust [23]. This historical stigma continues to color discussions around euthanasia, fostering strong resistance, particularly in the U.S. and Germany, where this historical context is still widely remembered. Consequently, any efforts to introduce or expand euthanasia practices are met with skepticism or outright rejection, as the historical and sociocultural associations shape lawmakers’ and physicians’ perceptions and moral judgments.

Legal constraints

Legally, the acceptance of euthanasia is significantly influenced by conservative laws that frequently prohibit or heavily restrict the practice, driven by concerns over the “slippery slope” effect. This phenomenon suggests that once euthanasia is permitted, the risk of losing control over the process increases, potentially leading to significant issues, as safeguards may be disregarded or breached [24].

Ethical constraints

From an ethical standpoint, one of the most prominent arguments against euthanasia centers around the principle of nonmaleficence—the ethical obligation to do no harm [25]. Many healthcare professionals and ethicists argue that euthanasia undermines this principle, asserting that intentionally ending a life, even with consent, is inherently harmful and contradicts the core duties of medical practitioners to preserve life and alleviate suffering through other means, such as palliative care [22]. This view is often reinforced by the concern that legalizing euthanasia could lead to a “slippery slope,” where vulnerable populations (e.g., older adults with frailty, disabled individuals, or those with mental disabilities or illnesses) might be coerced or subtly pressured into choosing death over life due to societal, familial, or economic factors [21]. The ethical objections also reflect concerns about the potential for abuse, where vulnerable individuals may not be fully capable of making such a profound decision, or where the practice might be used as an alternative to improve healthcare infrastructure and palliative care options [21].

These limitations reflect the complexity of balancing individual autonomy with societal values, historical legacies, and the moral responsibilities entrusted to medical professionals. Until these issues are addressed, the implementation of euthanasia will remain contentious, and the terminology surrounding it will continue to evolve in response to shifting social and cultural dynamics.

Future directions

As euthanasia continues to be a highly contentious issue worldwide, its future direction hinges on multiple interconnected factors, which need to be addressed collaboratively by policymakers, healthcare providers, ethicists, and the broader public. Given the sociocultural, legal, and ethical complexities described in this article, several key directions will likely shape the evolution of euthanasia practices and the discourse surrounding them.

Shifting sociocultural perspectives and acceptance

The increasing public acceptance of euthanasia, particularly in Western Europe, North America, and certain parts of Latin America, suggests that a cultural shift may be underway. As attitudes continue to evolve, particularly in societies with younger and more liberal demographics, the support for euthanasia is expected to rise, especially if framed in a manner that emphasizes dignity and individual autonomy in end-of-life decision-making. The movement toward adopting softer language, such as the proposed term “eumori,” could be instrumental in reshaping societal perceptions and overcoming historical stigmas associated with euthanasia.

Legal and policy developments

The legal landscape for euthanasia will likely evolve as more countries and jurisdictions consider its potential legalization. While concerns about the “slippery slope” effect remain a significant barrier, future legal frameworks should focus on stringent safeguards to protect vulnerable populations. For instance, laws may evolve to permit euthanasia under very specific circumstances, such as for patients with terminal illnesses or those with advanced, irreversible conditions, while ensuring that sufficient consent and rigorous oversight processes are in place [26]. Additionally, ongoing legal reforms may incorporate lessons learned from countries like the Netherlands and Belgium, where euthanasia is legal but regulated with strict guidelines, which could help mitigate concerns about abuse and misapplication [26].

Healthcare provider perspectives and training

Physicians will continue to play a crucial role in the implementation of euthanasia. Surveys show that healthcare professionals support euthanasia at lower rates than the general public, emphasizing the ethical principle of patient autonomy for terminally ill individuals. Increasing awareness of alternative terminologies could help reduce the negative connotations associated with euthanasia and ease the moral discomfort physicians and other healthcare providers feel.

Ethical reconsiderations

The ongoing ethical debates surrounding euthanasia will likely continue to center on fundamental principles like nonmaleficence (the obligation to do no harm) and the potential risks of coercion, particularly among vulnerable populations. As societies evolve, it will be critical to balance respecting individual autonomy and protecting those vulnerable to external pressures. Future ethical frameworks could further explore ways to safeguard patient autonomy while providing robust safeguards to prevent potential abuse, such as independent psychological evaluations, advance directives, and enhanced oversight by medical boards.

Global dialogue and international influence

The future of euthanasia will likely be shaped by ongoing international dialogue and the sharing of best practices among countries that have legalized euthanasia. As more countries consider legalizing euthanasia, global cooperation will be vital to ensure that the practice is implemented responsibly and with due regard for human rights. The role of international organizations, such as the World Health Organization and the United Nations, may become increasingly important in fostering consensus on the ethical and legal considerations of euthanasia, especially in light of diverse cultural perspectives.

Further research and public engagement

More research is needed to assess public opinion, physician attitudes, and the outcomes of euthanasia practices in regions where it is legal to better understand its complexities. Studies should focus on patient outcomes, the emotional well-being of healthcare providers, and the broader societal implications of legal frameworks of euthanasia policies. Public engagement initiatives, such as public consultations, education campaigns, and forums for dialogue, could also help bridge the gaps in understanding and pave the way for more informed and empathetic discussions about end-of-life choices.

A limitation of our research is the potential influence of cultural and linguistic biases associated with the terminology used. In suggesting a change to the term “euthanasia,” we have reflected a cultural bias influenced by historical associations, particularly in contexts such as Germany, where the term carries significant stigma due to its Nazi-era connotations. This cultural bias led us to suggest that modifying the terminology could contribute to reducing stigma or shifting public perception. However, some will argue this view may oversimplify the issue by neglecting the deeply rooted ethical, philosophical, legal, and emotional concerns that shape public and professional attitudes toward euthanasia. Although their concern is valid and creates a limitation in our manuscript, any broader conversation addressing these complex ethical issues should regard a linguistic shift as an integral component of the problem rather than a standalone solution.

The practice of euthanasia reflects a complex interplay of societal, cultural, ethical, and legal factors. Its growing acceptance over the past few decades signifies a transformative shift in end-of-life care marked by an increasing emphasis on individual autonomy and dignity. The legalization of euthanasia in numerous countries, particularly across Western Europe, mirrors a broader trend toward progressive policies in end-of-life care and a heightened respect for patient preferences.

Nonetheless, the terminology and history associated with euthanasia impose a burden that undermines broader acceptance. Therefore, we advocate for the adoption of euphemisms, such as “eumori,” as an initial approach to reshaping the discourse surrounding euthanasia and mitigating the stigma attached to its name. Embracing alternative terminology can empower healthcare professionals to evaluate and address barriers that hinder open discussions about euthanasia, patient autonomy, and preferences for end-of-life care within the clinical setting.

We thank the staff of Neuroscience Publications at Barrow Neurological Institute for assistance with manuscript preparation.

- Papadimitriou JD, Skiadas P, Mavrantonis CS, Polimeropoulos V, Papadimitriou DJ, Papacostas KJ. Euthanasia and suicide in antiquity: viewpoint of the dramatists and philosophers. J R Soc Med. 2007;100(1):25-8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680710000111

- Emanuel EJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Urwin JW, Cohen J. Attitudes and Practices of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79-90. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8499

- Death with Dignity. A Glossary of Terms for Discussion. Available from: https://deathwithdignity.org/resources/assisted-dying-glossary/.

- Beauchamp TL, Davidson AI. The definition of euthanasia. J Med Philos. 1979;4(3):294-312. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/jmp/4.3.294

- Picon-Jaimes YA, Lozada-Martinez ID, Orozco-Chinome JE, Montana-Gomez LM, Bolano-Romero MP, Moscote-Salazar LR, et al. Euthanasia and assisted suicide: An in-depth review of relevant historical aspects. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;75:103380. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103380

- Mroz S, Dierickx S, Deliens L, Cohen J, Chambaere K. Assisted dying around the world: a status quaestionis. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10(3):3540-53. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-20-637

- Frank M, Acosta N. Cuba quietly authorizes euthanasia. Reuters; 2023 Dec 22. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/cuba-quietly-authorizes-euthanasia-2023-12-22/

- Gilbertson L, Savulescu J, Oakley J, Wilkinson D. Expanded terminal sedation in end-of-life care. J Med Ethics. 2023;49(4):252-60. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/jme-2022-108511

- Piili RP, Louhiala P, Vanska J, Lehto JT. Ambivalence toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide has decreased among physicians in Finland. BMC Med Ethics. 2022;23(1):71. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-022-00810-y

- Ristic I, Ignjatovic-Ristic D, Gazibara T. Personality traits and attitude towards euthanasia among medical students in Serbia. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2024;59(2):232-47. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/00912174231191963

- Rathor MY, Abdul Rani MF, Shahar MA, Jamalludin AR, Che Abdullah ST, Omar AM, et al. Attitudes toward euthanasia and related issues among physicians and patients in a multi-cultural society of Malaysia. J Family Med Prim Care. 2014;3(3):230-7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.141616

- McCarthy J, Wood J. Majority of Americans remain supportive of euthanasia. Gallup; 2017 Mar 4. Available from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/211928/majority-americans-remain-supportive%20euthanasia.aspx

- Givens JL, Mitchell SL. Concerns about end-of-life care and support for euthanasia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):167-73. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.012

- Sheldon T. Andries Postma. BMJ. 2007;334(7588):320. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39111.520486.FA

- Rietjens JA, van der Maas PJ, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van Delden JJ, van der Heide A. Two decades of research on euthanasia from the Netherlands. What have we learnt and what questions remain? J Bioeth Inq. 2009;6(3):271-83. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-009-9172-3

- Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Evenblij K, Pasman HRW, van Delden JJM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, van der Heide A. Physicians' and public attitudes toward euthanasia in people with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(10):2319-28. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16692

- Donlevi K. Former Dutch prime minister and wife die ‘hand in hand’ in legal duo euthanasia. The New York Post; 2024 Feb 11. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/10/duo-euthanasia-former-dutch-prime-minister-dies-wife-dries-eugenie-van-agt

- Kouwenhoven PS, Raijmakers NJ, van Delden JJ, Rietjens JA, van Tol DG, van de Vathorst S, et al. Opinions about euthanasia and advanced dementia: a qualitative study among Dutch physicians and members of the general public. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:7. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-16-7

- Pitt MB, Hendrickson MA, Marmet J. Use of euphemisms to avoid saying death and dying in critical care conversations—A thorn by any other name. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(10):e2233727. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.33727

- McIntosh M. Medical aid in dying: Stop calling it ‘suicide’. Brewminate: A Bold Blend of News and Ideas. Available from: https://brewminate.com/medical-aid-in-dying-stop-calling-it-suicide/.

- Oregon Health Authority. Frequently Asked Questions: Death with Dignity Act: State of Oregon. Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/ph/providerpartnerresources/evaluationresearch/deathwithdignityact/pages/faqs.aspx. Accessed 2024 May 24.

- Srivastava V. Euthanasia: a regional perspective. Ann Neurosci. 2014;21(3):81-2. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5214/ans.0972.7531.210302

- Czech H, Hildebrandt S, Reis SP, Chelouche T, Fox M, Gonzalez-Lopez E, et al. The Lancet Commission on medicine, Nazism, and the Holocaust: historical evidence, implications for today, teaching for tomorrow. Lancet. 2023;402(10415):1867-940. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)01845-7

- Pereira J. Legalizing euthanasia or assisted suicide: the illusion of safeguards and controls. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(2):e38-45. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3747/co.v18i2.883

- Fontalis A, Prousali E, Kulkarni K. Euthanasia and assisted dying: what is the current position and what are the key arguments informing the debate? J R Soc Med. 2018;111(11):407-13. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/0141076818803452

- Marijnissen RM, Chambaere K, Oude Voshaar RC. Euthanasia in dementia: A narrative review of legislation and practices in the Netherlands and Belgium. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:857131. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.857131