Case Report

Dealing with Depression in Family Caregivers

Wai Hing HUI-CHOI*

School of Nursing, the University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

*Address for Correspondence: Dr. Wai Hing HUI-CHOI, School of Nursing, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; Email: [email protected]

Dates: Submitted: 01 March 2017; Approved: 24 March 2017; Published: 27 March 2017

How to cite this article: Wai Hing HUI-CHOI. Dealing with Depression in Family Caregivers. Clin J Nurs Care Pract. 2017; 1: 020-030. DOI: 10.29328/journal.cjncp.1001003

Copyright License: © 2017 Hui-Choi WH. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

Aims and objectives: By reporting the use of therapeutic nursing interventions to facilitate the process of change in a depressive elderly caregiver, this paper seeks to underline the importance of fitting interventions to individual clients.

Background: In assisting families of chronic illness sufferers, it must be remembered that the perceptions and functions of both clients and families are determined by family members, and that changes, if any, are made by those clients and families, rather than by nurses. However, nurses do play an important role in facilitating the process of change.

Design: This is a case report.

Methods: A case study of a depressive elderly caregiver is used to examine the use of therapeutic nursing interventions to facilitate the process of change with problem analysis, case conceptualisation and specific skills employed documented.

Results: The change from one therapeutic approach (Cognitive-behavioural therapy) to another (Narrative Therapy) facilitates enlisting the caregiver’s unique strengths, resources and competence to overcome the difficulties and challenges identified during the process of change. In dealing with depression in family caregivers, nurses should not only be flexible but also remain sceptical in using different approaches, with heightened awareness of the client’s circumstances.

INTRODUCTION

Many healthcare systems encourage cost-cutting, notably by shortening the duration of hospital stays, soliciting more assistance from and attributing greater responsibility to the families. Those with family members suffering from chronic disease find it particularly stressful. The physical burdens, strain, role fatigue, role overload and stress of family caregivers resulting from long-term care provision have much been reported [1]. In the case of stroke survivors, the caregivers’ psychological burden and needs often persist long after the patients have been discharged from hospital [2]. These caregivers experience strong feelings of responsibility, constant anxiety, decreased social activity and loneliness [3]. Their depression may even worsen that of the survivors and hence lead to poor responses to rehabilitation [4].

Interventions that attend to caregivers’ individual uniqueness are likely to produce positive outcomes. Brereton et al reviewed eight studies investigating stroke caregivers who were provided with training, education and counselling, social problem-solving partnerships, and psycho-educational support groups or programmes [5]. However, the studies were of low quality. In a meta-analysis study, various psycho-social interventions used showed insignificant effects on dementia caregivers [6]. Similar findings were reported in a longitudinal study (Wolff et al. 2009). Yet, in a larger review of interventional studies, counselling was found to provide the best chance of resulting in positive outcomes [7]. In family counselling and interviews, Wright and her colleagues strongly believe changes in the perceptions and family functions of clients and families facing chronic illnesses are determined by family members rather than nurses. To facilitate the process of change in an effective way, the recommended interventions should ‘fit’ the needs of clients/families, whose uniqueness and individual situations demand careful considerations [8-10]. Following Wright’s suggestions, certain programmes were designed to deal with the individual needs of caregivers. For example, in one 12-month post-stroke intervention study, the caregivers of the intervention group showed a better quality of care (p=0.03), with their stroke survivors less likely to be institutionalised (p=0.03) [11].

To obtain a full description of the interventions used, identify the mechanisms of change and describe the usefulness of the interventions, Wright further called for examination of the therapeutic interventions that clients/families and nurses engage in with one another [12]. The present paper describes therapeutic interviews between the author and a depressive 61-year-old Chinese woman, Polly, (a pseudonym to protect the client’s privacy) caring for her husband with stroke and dementia with the aim of underlying the importance of fitting interventions to individual clients.

When Polly first registered in a community clinic, she appeared very sad and was assessed using the General Depression Scale (GDS) [13]. She scored 12 out of a total of 15 on the GDS, clearly pointing to depressive symptoms. She refused psychiatric referral as she was strongly against medication. With aging knees, she limped a little when she walked. Polly used to live with her husband in a public housing unit till nine months ago, when the husband moved into an old-age home. Her three children, two boys and a daughter, were all married and lived apart from her.

Polly supported a heavy burden ever since her husband sustained severe mobility loss after a fall. He had a stroke ten years ago, and the attack was so severe that the doctor was not at all optimistic about his survival. But he pulled through in the end, and was discharged home after staying in hospital for a month. During the daytime, a neighbour was called in to look after him when Polly went to work. Nine months ago, Polly quit work to give her full attention to her husband, but caring for a dependent and immobile husband soon caused Polly multiple bodily pains. Reluctantly, Polly agreed to the family’s decision to send the husband to an old-age home, but continued to bring him home whenever she could to cheer him up. But she soon found this less feasible, as the husband’s mobility further decreased and her own shoulder and knee pains worsened. To compensate, Polly paid more visits to the old-age home to settle her husband, who now felt unconnected to many recent events but felt reassured when Polly talked about remote past experiences of the family. Because of the monotonous routine in the unit, Polly was enthusiastic about enrolling her husband in various activities. On one occasion, she took him out on an excursion. In her descriptions of the husband’s exciting experience, Polly admitted honestly that in the end she had not in fact enjoyed the outing at all, as there were too many things for her to work out and be cautious about. Apart from the physical strain of wheeling her husband around, her bag was overloaded with the things he needed, including diapers, food and drink. But Polly kept pushing herself to provide the best care she could for her husband.

However, the residential care was worrying and the husband’s behaviour was overwhelming. He had suffered repeated ‘accidents’, explained the health workers, resulting in bodily injuries such as skin breaks at the toes and falls from bed. But Polly had never made any complaints, worrying that the workers might lose their jobs if they were accused of anything. The accidents caused Polly great concern, but the only intervention she made at the old-age home was a strong request to be informed, by phone, of any adverse occurrences, such as falls, or whenever her husband was unsettled or behaving oddly. Polly referred to an incident where a new worker had put away her husband’s slippers when cleaning the floor. He had apparently lost control, thrown things around and argued fiercely with the worker. He had fought hard to get the slippers back and insisted on wearing them home. Polly, when informed of all this by the agency, had immediately had to rush in from home. With such embarrassing events happening repeatedly, Polly became highly anxious whenever her mobile phone rang. Lately, in one of her visits to the clinic, her blood pressure readings were notably high because of poor sleep the night before, when the husband had again had a fall.

According to systemic analysis, the first problem Polly presented was being ‘unable to accept and to cope with changes in the care of her husband’. Polly could not come to terms with the reality involving her own degenerative knee pain in providing care for her husband, whose physical and mental functioning was debilitated. Overwhelmed, Polly failed to meet the demands of caring for her husband, first at home, then in the old-age home. Her physical, psychological and social health was all tied up with the wellness of her husband, as shown by her high blood pressure readings, poor sleep quality, reduced social activity and round-the-clock attendance on the husband’s agitating and demands.

Another presenting problem was ‘shameful and guilty feelings because of stigmatisation and inadequate support’. Polly’s over-involvement seemed to relate to cultural influences and the lack of family support. She had received much questioning and criticism from family elders about sending her husband to the old-age home. In the Chinese culture, elderly people, whatever their degree of dependence, are expected to be cared for at home. Such expectations and practices are dominated by Confucian principles, with the belief in showing respect and obligation in care of the elderly strongly emphasising gender roles [14]. In Chinese families, wives, daughters and daughters-in-law are expected to be the main caregivers for dependent old people. In agreeing to her husband being sent into residential care, Polly felt ashamed and guilty for not fulfilling her expected role. Her feelings were intensified by socio-cultural stigmatisation and the negative comments of relatives. Polly therefore put more and more effort into caregiving till she became exhausted, physically and psycho-socially. But her efforts, in return, had not gained the empathy of her children, who saw structural constraints, notably working for a living, as restricting their caregiving and display of filial piety, though the filial piety value might have been internalised. The internalisation of caregiving values and a refusal to perform physical care are now commonly found in younger people [14].

The third presenting problem was ‘lack of assertiveness in seeking better care for her husband’, which had originally developed from Polly’s family upbringing. In the interviews, Polly showed great consideration for others, but little for herself, and this remarkably considerate nature could be traced back to her childhood. She was brought up in a family of low socio-economic status, and though she was not the eldest child she used to take care of her siblings when her elder sister failed to do so. As a middle child, Polly played a placating role when there were fights between her brothers and sisters, and was also assigned the most household chores. Such an upbringing had given Polly a perception of herself that emphasised providing for and supporting others, and this strong sense of responsibility was extended to caring for her institutionalised husband. With her placatory attitude towards the workers at the residential unit, Polly had never filed any complaints of neglect against the institution, as she would not wish to be stereotyped as a trouble maker. As a result of all this, her worries about her husband’s welfare were escalating, to the extent that she became anxious about even answering the telephone.

INITIAL INTERVENTION

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) [15], is regarded as one of the most effective non-pharmacological interventions in treating depressive clients. It believes a person’s mood is directly related to his or her patterns of thought, not the situation the person is in. Hence, negative, unrealistic perception of the situation affects the person’s mood, sense of self, and behavior. The goal of CBT is to help the person learn to recognize cognitive distortions, and replace them with healthier ways of thinking in order to change his or her emotions and behavior. In interview sessions, the person is taught how to identify distorted cognitions through a process of evaluation. The person learns to discriminate between his or her own thoughts and reality as well as the influence that cognition has on his or her feelings. Tasks or homework are given to help the person recognize, observe, and monitor his or her own thoughts and finally challenges the unhelpful beliefs.

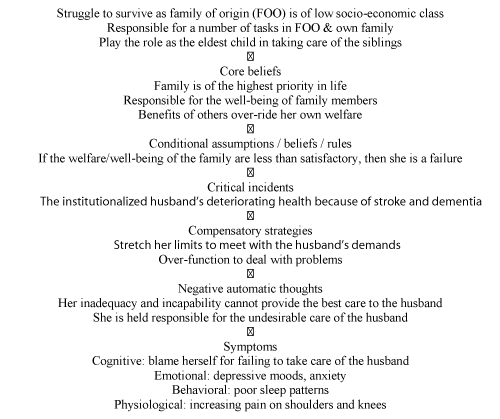

Cognitive-behavioural therapy was initially used to resolve Polly’s problems. After CBT had been applied in four sessions, Polly’s problems were conceptualised (Figure 1). In the light of this case conceptualization, focus was put on tackling Polly’s over-responsible perceptions, which had resulted in her going to extremes as a caregiver. As the interviews went on, some positive effects, particularly in the early sessions, were evident, but increasing resistance was felt later. Certain difficulties were identified and, to illustrate these more precisely, scripts that gave vivid descriptions were used. These scripts were retrieved from the audio recordings that had been made (with Polly’s consent) during the interviews, for designing future sessions for her. Approval from the ethics committee of the institution was sought.

One of the difficulties was ‘devaluation under the influence of Chinese culture’. It was noted that the directive pattern typically used in CBT could not change very much the firmly rooted cultural pressures on Polly. The traditional Chinese system exemplified by this family was a patriarchal one with deference accorded to those in higher authority, the ‘elders’. Roles were strongly defined for each member within the family structure, and the subjection of individual rights, desires, wants or needs to the greater collective good of the family was expected of everyone [16]. In the interviews, very strong defensive responses were received, some of which were made when Polly took the initiative to express her lost hopes, while others came when the author wanted to correct her thinking. Two of her remarks are quoted here as illustrations.

The first was a self-defeating thought developed from the family’s unfulfilled collective goals. After the couple’s earlier hard struggle for a living, throughout the years, they had been planning a more relaxing, pleasant time together in their retirement. Polly longed to share this late stage of life with her husband, but when that long-planned wish never came true she saw herself as a great failure. As she exclaimed:

‘(sighing) I have never done any bad deeds and never sought riches or fame, but I still don’t get what I want!’

When she was asked to comment on whether people who could not get what they wanted in life had failed in the struggle, she re-emphasised the point that she did not ask for any material rewards. At the end, she even questioned herself, whether she had unknowingly performed badly in some matter that deserved the penalty. Polly produced the second remark when unhappily describing her children’s lack of appreciation of what she had done. She could not agree with them when they always asked her not to overburden herself in the caregiving role. When the author attempted to give credit to her dedication and contribution in raising the children, without much thought she replied:

‘Every mother would love and nurture her children because it is you who bring them into the world…’

Unexpectedly, a follow-up to the conversation had lit a spark. When Polly was asked to comment on a recent news headline about children who had suffered parental neglect or even abuse, some of whom, as a result, had committed crimes such as theft, her attitude took a turn different from the usual defensiveness. Instead of repeating what she had said before, her remark, surprisingly, was a defence of others, not of herself. Her exact words were:

‘Though they are thieves, to me, they all have good reasons to steal. Of course, I do not want to see my children falling into such situations. This was what I taught them when they were little. My children are so familiar with this that they sometimes make a joke of it, saying, ‘Ha, mum, we know, “Thieves have good reasons (to steal), right”?’

For her, ‘good’ reasons were simply those that served good purposes. She went on to say that one such good reason might be the need of a poor family to get money to send a sick family member for medical treatment. Another difficulty encountered in using CBT was the ‘suppression of emotions delaying cognitive advancement’. In almost every session, Polly asked for quick solutions to her problems. To address that, a prescriptive approach was increasingly used. It was only on one or two occasions in later sessions that Polly’s long-suppressed emotions were finally disclosed. Some thoughts that were connected to these underlying emotions seemed to bother her. She knew she should not have such thoughts but simply could not help it. Her deep grief and wild thoughts were evident in one extreme account she gave:

‘Yes, I would be willing to sacrifice my own leg if that could save his…Even though none of them (her children) would support this idea, I would still go ahead because he has nothing (her husband had lost mobility in both legs)!’

After her talking further about the lack of understanding and appreciation on the part of children and relatives who kept criticising her, Polly was asked to evaluate herself in the multiple roles, as a mother, wife and income earner, that she held in the family. She said:

‘I probably get 85 out of 100…I cannot get 100.’

It was notable that the self-rated score was in fact a self-defeating score. Polly declared that she had done her very best but was still far from deserving a high ranking. The author noted Polly’s low ranking of herself was connected to factors such as the difficult circumstances of her life, the failure to gain the understanding of her children, and the continual criticism from the relatives. Even when she was reminded of these external situations, which were not under her entire control, she still refused to reconsider giving herself a higher score.

The last but not the least difficulty encountered was that ‘little hope could be instilled’. In reviewing the husband’s deteriorating health since the first fall had occurred nine months earlier, Polly felt more and more burdened from month to month. At the beginning, she had held out some hope for her husband’s full recovery, even though it might take a long time. She pushed herself hard to maintain a positive attitude and felt better when she could do that. But, with the husband’s repeated falls and other injuries sustained at the old-age home, Polly realised the road to recovery had no end, and she became depressed. She continued to hold a gloomy view of her husband’s future health prospects, though the problem-focused psychotherapy of CBT, which mainly deals with the present issues and not the future, was being implemented at the time. Efforts were nevertheless made to modify her negative thoughts about her husband’s health. For example, when she was asked to give an overall comment on his health status, she showed a somewhat positive view, while on the other hand displaying a passive involvement and lack of choice.

‘I would say it is a piece of good luck in all the bad luck. As I said before, he nearly died but was rescued from the stroke ten years ago. He might have died then…I see this as a gift from God, which I cannot refuse. It is all pre-arranged.’

In almost each of the sessions, Polly was given homework to do. For example, she was asked to keep a diary of thoughts which were brought to the following session for discussion. Some of the thoughts recorded were ‘I should have done better”, “Nobody likes me”, and “I am a failure”. However, little progress was made in the discussions.

CHANGE INTERVENTION

Shifting to another therapeutic approach was considered at this point. However, there would have to be adequate justification and assessment of the benefits that any new approach might bring to Polly.

Justification was drawn from a few observations. First, as reported in the later part of the CBT interviews, Polly began to see the distortions in certain of her thoughts. However, her persistent defensive response to protect her long-term perceptions, thinking, habits and behaviour remained strong. The author had a feeling that it would require several extra sessions before that aspect could be dealt with. Second, CBT tends to deal with problems pertaining to an individual; but Polly’s issues were closely tied to various family relationships. To resolve her problems in some way, it would be good if some of the family members could be present at the interviews, although the author knew it was not really feasible. But the author was impressed by Polly’s principles for living, which, when they were first presented, did not strike the author as an important link. That was when Polly repeatedly and strongly rejected the author’s suggestion that she negotiate with the nursing home to avoid future falls and injuries to her husband, which she interpreted as a threat to the workers there. She worried the people involved might be fired as a result of her complaints. As her stories unfolded further, the author began to connect the bits and pieces together, and her consideration of others then became apparent - for instance, the preaching to her children about the possible ‘good’ reasons behind acts of theft. To Polly, being considerate towards others seemed to be a larger and more important principle that even overrode her concept of the family.

With these hypothesis in mind, the author affirmed that the alternative approach would be effective in enhancing a positive view of the self, facilitating emotional expression and, most importantly, re-gaining hope through loss. A measure of narrative therapy was attempted, a practice using stories that people tell themselves and others about their lives which validates such ‘local’ knowledge to explore alternatives and new meanings in providing self-coherence to the client in the consultation [17]. In contrast to modernistic view in which universal truth and objectivity are highly regarded, the practice considers the person, invisibly influenced by culturally and politically dominated beliefs and assumptions, and indoctrinating himself or herself into narrow and self-defeating views. Most of the problem-saturated narratives, which often fail to give a full account of the person’s life experience, make that person think of himself or herself as inadequate. Often, the inadequacy also involves relationships because they, rather than individuals, are considered to constitute the foundations of society. According to the concept of ‘self through other’ in the construction of the relational self [18], we are to view ourselves as relational outcomes.

The use of therapeutic stories has shown promise in addressing the caregiving burden. Relying on research findings from the 1970s and 1980s, to include a person’s highly individualised responses to a dependent older person’s impairments [19]. Zimmerman have identified important advantages of the narrative approach in relieving therapeutically the caregiver’s burdens [20]. In their elaboration, life narratives develop through time, and the focus of the therapeutic encounter can therefore be on the effects of the narratives rather than the causes. The approach focuses the narrative metaphors on experience rather than on information as the organising structure of the narratives. In applying the narrative approach to Polly’s case, the author aimed at promoting assertiveness through enhancing a positive view of herself, facilitating emotional expression and re-gaining hope through loss. Two main techniques were used in the three interview sessions, externalising or re-authoring conversations, each of which is reported below.

The author began by asking Polly to talk about her experience in caring for her husband rather than to identify activities that made her anxious. In the conversation, Polly expressed herself quite comprehensively. Every time the phone rang, she expected the call to be from the nursing home, and would feel tense and insecure, in this way:

‘I really cannot tell what will happen the next moment (considering the phone can ring at any time)!’

Polly was helped to externalise the problem, which she likened to ‘an anxious ant on a hot pan’, using externalising conversations. The goal of the approach is to separate people’s identities from the problems they face. In externalising language, the implication is that the problem is not possessed by the person but dominates that person’s life. The concepts whereby ‘the problem is the problem’ and the client is not [17] are expected to have a liberating effect, when the person shifts from having the problem to having a relationship with it. The person becomes more able to experience the capacity to intervene in his or her own life and relationships. Using the externalising technique, Polly’s expression ‘I am anxious’ became ‘I am currently experiencing anxiousness’. The problem, “anxiousness”, was separated from Polly. As problems are dependent on their effects for their survival so by standing up to a problem and not allowing it to affect those, clients cut off the “life-support system” of the problems [17]. Polly was asked how the anxiousness affected her experience of herself, how it was able to make her do what it wanted, and how often she was able to stand up to it.

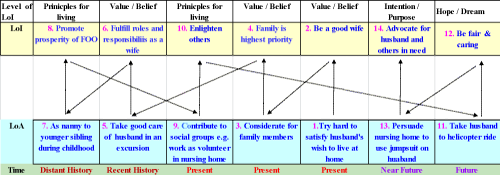

As life narratives are not limited to current encounters but develop through time, the author used a re-authoring technique, first inviting Polly to talk about her past experience of caregiving, and then plotting, together with her, a few desirable stories of the future. It is suggested that evidence of competence relative to the problem can be collected by going through people’s history to serve as the start of new narrative regarding what kind of people they are [17]. Practically, questions are asked on what past and present victories over the problem says about the client. Often, the historical purview is also expanded beyond circumstances related to the problem to find more evidence to reinforce the new self-narrative. The central point of re-authoring conversations is retrieving the landscape of action and landscape of identity. The landscape of action is obtained by asking about events, and circumstances while the landscape of identity emphasizes on realizations, and accorded values (Figure 2).

Figure 2 illustrates Polly’s regenerated identity by plotting the landscape of action and the landscape of identity. As shown in the figure, one outstanding event had occurred quite recently. In spite of the caregiving burden, she had been involved in volunteer work at a nearby social service centre. Polly discussed the husband’s problem with the use of diapers at night with the centre workers. In the discussion, she was advised to consider using a jumpsuit which could stop incontinent people suffering from dementia from pulling off the napkins. Polly enthusiastically took the idea back to the old-age home where her husband stayed, without knowing that it was only the beginning of a small ‘battle’.

Figure 2: Polly’s regenerated identity using reauthoring conversations. Note: LoI is landscape of identity; Loa is landscape of action; FOO is family of origin; The zigzaging between the landscapes indicates the flow of storylines.

Polly had to deal with administrative personnel at different levels. At the beginning, the manager of the home was reluctant to accept what she proposed. While no jumpsuit had ever been used in the home, the manager had two concerns. One was about the additional time that the workers would need to put the jumpsuit on her husband. Another was about receiving comments from other residents and relatives when they saw him wearing it - they might be concerned if special treatment was being provided for individual residents. Polly tried hard to convince the manager. After several sessions of negotiation, the manager finally agreed to seek opinion and support from the occupational therapist. Polly continued to lobby the workers who provided day-to-day care for her husband until, only recently, she received full approval for her husband to have the jumpsuit – an outcome that was regarded as unique.

With this experience of pursuing and achieving her goal, Polly was invited to ascribe meanings to it. In doing so through actively accounting for the unique outcome, re-describing herself, others and relationships, or speculating about new possibilities accompanying the outcome, Polly began to re-author her life and relationships. In highlighting her considerate nature and principles, a preferred story was made available for performance. She became more aware of possible future accomplishments if she continued to advocate improvements for the people in the old-age home. She was gently reminded that the beneficiaries included but were not limited to her husband. In return, improved care in the home would give her peace rather than more anxiety. She became more willing to discuss further the care of the husband with the agency. The new role that she took up was very different from that of the trouble-maker she had previously perceived.

RESULTS

By reporting the case, this paper used more than one therapeutic approach in an attempt to imbue an elderly female caregiver with the strength and hope to help her through the travails of taking care of a chronically ill husband. Specifically, the change from one therapeutic approach (Cognitive-behavioural therapy) to another (Narrative Therapy) facilitates enlisting the caregiver’s unique strengths, resources and competence to overcome the difficulties and challenges identified during the process of change. The unfulfilled social, cultural, role obligations involved in the family caregiving had made the process of change challenging.

DISCUSSION

It is important to address the way care of family caregivers is neglected. Studies have associated the perceived quality of life of caregivers with the nature of available social support [21,22], but psycho-social support should be expanded beyond the conventional services generally offered. Family-based workers must reorient their interventions, which are at the moment primarily geared towards the chronically ill, instead of considering family caregivers as co-clients of the services. In other words, what is called for is a more global approach centered not only on the needs of those receiving direct care but also on the biological, psychological and social needs of family caregivers. Interventions have been attempted to address these needs. In a report that critically analyzed 39 studies on family caregiver interventions, most caregiver interventions were concluded useful in improving caregiver outcomes [23]. The encouraging evidences came in time for the increasing demand of family caregivers, particularly in countries with an aging population. A nationwide call for health care delivery system reform that elevated family-centered care alongside patient-centered care was recently made [24].

It is frequently noted that not many people utilise mental health services and even fewer will self-refer [25]. For various reasons, there is often reluctance to seek help for mental health problems. If help is sought, it is often when a crisis occurs and, if treatment is initiated, it is often terminated prematurely. It is not surprising that the added caregiving strain due to socio-cultural obligations and stigmatization may create barriers to seeking help. If the quality of life of family caregivers who look after the chronically ill is to be seriously considered, routine screening of those caregivers would clearly be of assistance. The screening or assessment should begin well before hospital discharge and be regularly performed. According to a systematic review study on hospital discharge planning for frail old people, assessing the impact of patient discharge on family caregivers was recommended [26].

It is worth noting that no single theoretical approach can comprehensively cover the complexities of human behavior taking consideration of the wide range of personalities and problems facing family-centered workers. However, workers who are familiar with different therapeutic approaches have the advantage to tailor their approach to the needs of the individual client to enhance the success of the process of change. These workers are encouraged to adapt and integrate more therapeutic ideas because clinical reality may not be exactly the same as the case examples learnt from textbooks that often focus on only one theoretical approach.

CONCLUSION

Bearing cost-effectiveness and quality of care in mind, family-centred workers should beware of unspoken socio-cultural obligations and stigmatisation which can add further burdens to the challenging tasks of family caregiving. They should not only be flexible but also remain sceptical in using different approaches, with heightened awareness of the client’s circumstances. For the increasing demand of family caregivers, they should consider putting family practice at the top of their agendas.

REFERENCES

- Choi-Kwon S, Kim HS, Kwon SU, Kim JS. Factors affecting the burden on caregivers of stroke survivors in South Korea. Archives of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2005; 86: 1043-1048. Ref.: https://goo.gl/DnH5pW

- Plank A, Mazzoni V, Cavada L. Becoming a caregiver: New family carers' experience during the transition from hospital to home. J Clin Nurs. 2012; 21: 2072-2082. Ref.: https://goo.gl/VHP8R8

- Northouse L, Williams AL, Given B, McCorkle R. Psychosocial care for family caregivers of patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012; 30: 1227-1234. Ref: https://goo.gl/zysY9F

- Williams AL, McCorkle R. Cancer family caregivers during the palliative, hospice and bereavement phases: A review of the descriptive psychosocial literature. Palliative Support Care. 2011; 9: 315-325. Ref: https://goo.gl/zg9Nge

- Brereton L, Carroll C, Barnston S. Interventions for adult family carers of people who have had a stroke: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2007; 21: 867-884. Ref: https://goo.gl/mTIhzq

- Schoenmakers B, Buntinx F, De Lepeleire J. Supporting the dementia family caregiver: The effect of home care intervention on general well-being. Aging & Mental Health. 2010; 14: 44-56. Ref: https://goo.gl/A0K4Rr

- Van Heugten C, Visser-Meily A, Post M, Lindeman E. Care for careers of stroke patients: Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2006; 38: 153-158. Ref: https://goo.gl/AAE65x

- Wright LM, Levac AM. The non-existence of non-compliant families: The influence of Humberto Maturana. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1992; 17: 913-917. Ref: https://goo.gl/7XmvwH

- Wright LM, Watson WL, Bell Beliefs JM. The heart of healing in families and illness. 2001; 35. Ref: https://goo.gl/z8op4b

- Wright LM, Leahey M. Nurses and families. A guide to assessment and intervention. Philadelphia, F.A Davis. 2005. Ref: https://goo.gl/uAdG3t

- Shyu YIL, Kuo LM, Chen MC, Sien-Tsong C. A clinical trial of an individualised intervention programme for family caregivers of older stroke victims in Taiwan. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2010; 19: 1675-1685. Ref: https://goo.gl/rhYjLR

- Bell JM, Wright LM. Research on family interventions, In Families and health: A systemic approach in nursing care. 2007.

- Radloff LS. A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977; 1: 385-401. Ref: https://goo.gl/9RSD86

- Chappell NL, Kusch K. The gendered nature of filial piety-A study among Chinese Canadians. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2007; 22: 29-45. Ref: https://goo.gl/0JLh63

- Beck AT, Brad AA. Depression: Causes and treatment. University of Pennsylvania Press. 1967. Ref: https://goo.gl/tjKbvS

- Chan CLF, Chui EWT. Association between cultural factors and the caregiving burden for Chinese spousal caregivers of frail elderly in Hong Kong. Aging & Mental Health. 2011; 15: 500-509. Ref: https://goo.gl/9t0UO8

- White M, Epston D. Narrative means to therapeutic ends 1st Edition.

- Gergen KJ, Gergen M. Social Construction: Entering the Dialogue Taos Institute Publications. 2004. Ref.: https://goo.gl/7DcTJy

- Hadjistavropoulos T, Taylor S, Tuokko H, Beattie BL. Neumpsychological deficits.caregivers perception of deficits and caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994; 42: 308-314. Ref: https://goo.gl/Akpp3w

- Zimmerman JL, DickersonVC. Using narrative metaphor: Implications for theory and clinical practice. Fam Process. 1994; 33: 233-245. Ref: https://goo.gl/Nld7oU

- Roth DL, Perkins M, Wadley VG, Temple E M, Haley WE. Family caregiving and emotional strain: Associations with quality of life in a large national sample of middle-aged and older adults. Quality of Life Research. 2009; 18: 679-688. Ref: https://goo.gl/JEPhKR

- Thomson P, Molloyb GJ, Chung ML. The effects of perceived social support on quality of life in patients awaiting coronary artery bypass grafting and their partners: Testing dyadic dynamics using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2012; 17: 35-46. Ref.: https://goo.gl/C51RD5

- Bakas T, Clark PC, Kelly-Hayes M, King RB, Lutz BJ, et al. Evidence for stroke family caregiver and dyad interventions: A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association and American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014; 45: 2836-2852. Ref: https://goo.gl/PvPteU

- National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Families caring for an aging America. 2016.

- Eaton J, McCay L, Semrau M, Chatterjee S, Baingana F, et al. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011; 378: 1592-1603. Ref: https://goo.gl/4uFDgb

- Bauer M, Fitzgerald L, Haesler E, Manfrin M. Hospital discharge planning for frail older people and their family. Are we delivering best practice? A review of the evidence. J Clin Nurs. 2009; 18: 2539-2546. Ref: https://goo.gl/ODs58I